Foreword

Jess Blair, Director, Electoral Reform Society

Openness and transparency are the key foundations of any democracy. But today we find too much of our politics is shrouded in secrecy. Too often voters remain unsure about who is behind the messages they read, who is behind the information that shapes their political views, and ultimately their votes. In no area is this truer than online campaigning.

Nine months on from the general election, we still have little idea how much money was spent in the campaign. But even when the data is published by the Electoral Commission, huge gaps will remain in our understanding of how voters were targeted – and by whom. Democracy is about empowering citizens so that they can actively take part in our political processes and make an informed decision at the ballot box. Transparency, fairness and accountability in political campaigning are key to ensuring this is possible. But while technology offers huge opportunities for political engagement, the current system – if it can be called that – is an unregulated Wild West.

Indeed, the Electoral Commission’s own post-election research found that ‘[m]isleading content and presentation techniques are undermining voters’ trust in election campaigns’ and that the ‘significant public concerns about the transparency of digital election campaigns risk overshadowing their benefits’.

This report, commissioned by the Electoral Reform Society and written by Dr Katharine Dommett and Dr Sam Power, sheds light on campaigning in the 2019 general election.

For the first time, the authors reveal how much was spent on social media platforms by campaigners and parties during the election, and track the rise of non-party ‘outriders’, with all the associated secrecy.

However, it’s not enough to just point out the risks. Dommett and Power also summarise the many sensible, proportionate and easily implementable recommendations, around which there is broad and cross-party consensus, as to how we can restore trust in our democratic processes. These reforms would shine a light on the murky world of unregulated online campaigning, focusing on five key areas: 1. Money; 2. Non-party campaigns; 3. Targeting; 4. Data; 5. Misinformation.

Many of the recommendations in this report echo existing calls to modernise electoral law to help rebuild trust in our democratic system. Recommendations include closing funding loopholes, creating national standards for social media ad transparency and ensuring voters can easily see who is targeting them and why.

Since we published our report Reining in the Political Wild West in 2019, countless calls have been made across the political spectrum in support of reform and there continues to be strong and long-standing cross-party support to tame the unregulated Wild West of online political campaigning.

Yet despite repeated calls for reform, little action has been taken. Strikingly, far from becoming more transparent, the authors find that in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, parties and campaigners have become even more cautious about disclosing information about their campaign activities online.

In terms of progress, the most significant step has been the launch of a consultation on extending the use of imprints to include online election material – a necessary step, but which on its own is woefully insufficient.

Such limited efforts have further been undermined by alleged threats to abolish the Electoral Commission if it cannot be ‘radically overhauled’. Rather than enhancing the Commission’s powers and resources so that it can tackle the challenges of the modern age, the body tasked with protecting our democracy is under unprecedented attack.

With elections due to take place across the UK in May 2021, we cannot let the urgent task of ensuring our electoral integrity be kicked into the long grass once more.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Doug Cowan, Josiah Mortimer, Jon Narcross and Michela Palese for their help with this report.

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

- Calls for greater regulation of digital campaigning have been growing in recent years.

- Since the 2019 general election, the government has taken only modest steps towards reform: launching a technical consultation on digital imprints. At the same time, the governing party has issued a threat to the very organisation vital in scrutinising electoral malpractice today.

- In this report, we revisit what we know about the 2019 general election to show why this action is insufficient, and why there is an urgent need to reform electoral law.

- We ask five questions to highlight areas of concern:

- What was being spent?

- Who was campaigning?

- Who was seeing what?

- How was data being used?

- What was being said?

- We show that nearly a year on from the election, the failure to reform electoral law means we still cannot answer these questions. However, we can estimate from our research and the limited publicly available data that the 2019 general election saw a surge in online campaign spend, and non-party campaign activity.

- In doing so, this report reveals:

- In the six weeks before polling day in 2019, the Conservative Party raised more money in donations than all other parties combined during the same pre-poll period in 2017. But little information is available about any of the main parties’ spending online or offline, not least in terms of how they targeted voters.

- Political party spending on platforms is likely to have increased by over 50 percent in 2019 compared to 2017, with around £6 million spent on Facebook and just under £3 million on Google by the three main UK-wide parties.

- The rise of the ‘outrider’: adverts placed by national parties constituted only a fraction of the total campaign spend. Voters are too often kept unaware of who is behind these opaque outfits. Sixty-four of these organisations registered in 2019 as a whole and 46 were registered after the election was (officially) confirmed on 29 October.

- Social media giants’ online ad archives – set up to provide a veneer of political transparency – are insufficient and often error-prone.

- In 2019, the Conservatives invested dramatically more in Google than other parties – almost triple Labour’s spend.

- According to new analysis of Facebook data, 88 UK organisations were coded as non-party campaign groups during the 2019 election. These groups placed 13,197 adverts at a calculated cost of £2,711,452. It can be difficult for voters to work out who is behind campaign material from a non-party actor.

- As such, it is currently ‘exceedingly difficult’ if not impossible to uphold the principles of the UK’s foundational electoral legislation.

- We review over 30 existing recommendations for change in relation to five key areas: money, non-party campaigns, targeting, data and misinformation, drawing out many points of consensus.

- The government has already committed to legislating for digital imprints, yet has thus far not set out a clear timeline as to its implementation. But far more remains to be done beyond digital imprints. We highlight 10 key recommendations:

- Require campaigners to provide the Electoral Commission with more detailed, meaningful and accessible invoices of what they have spent, and to subdivide spending returns to provide more precise information about online campaigning. This will allow for greater scrutiny of and transparency around what is being spent online, and on which platforms, at both national and local levels.

- Strengthen the powers of the Electoral Commission to obtain information outside of an investigation, to share information with other public agencies, to increase the maximum fine, to investigate and sanction candidates for breaking the rules. The Electoral Commission needs sufficient resources and powers to be an effective regulator in the digital age.

- Implement shorter reporting deadlines so that financial information from campaigns on their donations and spending is available to voters and the Commission more quickly after a campaign, or indeed, in ‘real time’. This would enhance transparency by ensuring voters can see who is spending and receiving money during the course of a campaign, not many months later.

- Regulate all donations by reducing ‘permissibility check’ requirements from £500 to 1p for all non-cash donations, and £500 to £20 for cash donations. The rise in online campaigning means that current thresholds for permissibility checks are woefully out of date and can be easily exploited by breaking up donations into smaller sums, raising the risks of foreign or unscrupulous interference.

- Create a publicly accessible, clear and consistent archive of paid-for political advertising. This archive should include details of each advert’s source (name and address), who sponsored (paid) for it, and (for some) the country of origin.

- New controls created by social media companies to check that people or organisations who want to pay to place political adverts about elections and referendums in the UK are actually based in the UK or registered to vote here.

- New legislation clarifying that campaigning by foreign organisations or non-UK residents is not allowed, and that campaigners cannot accept money from companies that have not made enough money in the UK to fund the amount of their donation or loan.

- Legislate for a statutory code of practice for the use of personal information in campaigns. This would clarify the rules surrounding how parties and campaigners use personal data for political purposes and ensure compliance with the law.

- A public awareness and digital literacy campaign which will better allow citizens to identify misinformation.

- Rationalise electoral law under one consistent legislative framework. Current electoral law is piecemeal, complex and dates back to the Victorian age, with little having changed since then. It needs to be modernised and simplified with urgency.

We argue that the new ‘Wild West’ of political campaigning presents an urgent challenge for democracy, but also an opportunity to boost public confidence in the integrity of elections.

Introduction

Katharine Dommett and Sam Power

Over the last few years, calls for the regulation of digital campaigning have been growing in the UK. Committees in the House of Commons and Lords, groups of MPs, regulators, think tanks, charities and campaign groups have been stressing the need for urgent electoral reform.

Yet nearly a year on from the 2019 general election campaign, the only concerted action taken by the government has been to launch a consultation on digital imprints. This change, first recommended by the Electoral Commission back in 2003, is long overdue, but it also only scratches the surface of the problem. And at a time when the Electoral Commission is more important than ever – needing new powers and competencies – we have witnessed growing threats to its future.

In this report, we look at the case for strengthening – not stymying – democratic oversight by examining what we know about the use of digital technology at the 2019 general election. Posing five questions, we show why there is a need for urgent action that extends far beyond digital imprints.

Specifically, we ask:

- What was being spent?

- Who was campaigning?

- Who was seeing what?

- How was data being used?

- What was being said?

Looking at examples from the 2019 general election, and presenting new analysis of Facebook and Google’s advertising archives, we demonstrate the case for reform. We also review the recommendations from a series of reports and inquiries to outline what has so far been proposed to address these trends. Through this report, we shed fresh light on the need for urgent action and the demand for far-reaching reform.

What was being spent?

Money spent in campaigns

Within the current system of electoral oversight in the UK, there is a well-established principle that there should be transparency around the money spent in campaigns. Indeed, the Electoral Commission is committed to providing a ‘trusted and transparent system of regulation in political finance’. This involves limiting the amount of money that can be spent by any candidate, party or campaign in an election to ensure a degree of financial parity, and providing information about the actors who are financing and supporting campaigns.

In recent years, the rise of online campaigning has prompted new questions to be asked about our understanding of the money being spent in election campaigns. Trends such as online donations, claims of foreign interference and the lower costs of campaigning online, have led people to ask whether there is enough oversight, and whether current rules are fit for purpose.

What are the rules?

Political parties and third party campaigns are subject to regulation largely set out under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA 2000). The regulations are based around four key principles:

- Transparency: that we should know who is donating money to political actors, and how the political actors are spending this money.

- No foreign interference: that those attempting to influence the political process with money are based within the UK.

- No undue influence: that the money spent does not cause undue influence on policy making decisions, or distort the political landscape at elections.

- Public confidence: that the finance regime should be designed in such a way that it engenders confidence in politics, not cynicism.

Within these principles, there are regulations around elections and spending, donations and disclosure:

- Elections and spending: national campaign spending limits (£30,000 per contested constituency) and local (candidate) spending limits (on average about £15,000 during the campaign) apply within a regulated period.

- Donations: foreign donations are banned to parties and candidates (but £500 and £50 respectively are allowed). Anonymous donations are limited at £50. There is no maximum donation limit for those on the electoral roll.

- Reporting: all donations over £7,500 (to political parties) must be declared to the Electoral Commission. During an election, all parties must submit six weekly pre-poll election reports of all donations they receive over £7,500. Third party campaigners (‘non-party campaigns’) wishing to spend over £20,000 in England and £10,000 in the rest of the UK during the election must also register with the Electoral Commission. They must submit details of any donation they receive over £7,500 in the six weekly pre-poll election reports.

The data declared to the Electoral Commission provides the most accurate account of the money political parties and (some) third party campaigners spend and receive. The database itself has been described as ‘effectively world leading’ by international political finance experts. However, these reporting requirements are often not made public for many months until after the event. While regulations require parties and campaigners to report donations during an election, they are given far longer to return official spending records. This means that the ‘official story’ about what was spent at an election is not told until well after polling day. Indeed, over nine months after the 2019 general election, spending returns made by the major political parties have not yet been published by the Electoral Commission.

Even once these reports are published, the detail provided on digital campaign spending will be minimal (see Dommett and Power, 2019). There is currently no requirement to declare whether money was spent on digital technology or offline campaigning. This means that official insights are not only often late in arriving, but also lack sufficient detail to allow us to understand what was happening online.

For people interested in digital campaigning, there are some unofficial sources that can be used to gain insight. Companies such as Facebook and Google have become somewhat more transparent about activity on their platform, providing rough breakdowns of spending on political advertising through publicly available advertising archives. These archives have been widely criticised as difficult to use, unreliable and lacking in detail, but it is possible to use this data to get a sense of how much money campaigners were spending on online adverts.

So, what do we know about money in the 2019 general election?

Looking first at the Electoral Commission returns we can see very little. Reports of spending from national and local parties, and from registered third party campaigns are still not available, over nine months after election day. Looking at the information on donations that is available, we can currently only glean descriptive information about the kind of money political parties (and non-party campaigners) were raising in the six weeks leading up to the election. The story here is that the Conservative Party raised far more money in donations than its two primary challengers (see figure 1), with nearly £19.5 million in overall donations during the pre-poll reporting period (as compared to Labour’s £5.1 million and the Lib Dems £1.25 million).

Figure 1: Weekly donations (over £7,500) at the 2019 general election as reported to the Electoral Commission as pre-poll donations (Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat)

Indeed, the £19.5 million the Conservatives raised in this period is greater than the sum total of reported donations to all political parties in 2017 during the same pre-poll period, which stood at nearly £18.7 million. In general, 2019 saw donors that were far more willing to part with their cash than in 2017 – the total reported donations topped £30.4 million (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Weekly donations (over £7,500) at the 2017 and 2019 general elections as reported to the Electoral Commission as pre-poll donations (all party)

On spending, some more immediate insight is provided by the tech companies’ transparency archives.

How did spend compare across the platforms?

Before delving into the detail, it is important to say that each company provides information about money in a slightly different way, and often lacks precision in their reporting. In its advertising archive, for example, Facebook only provides brackets for advertising spending (i.e. <£100 or £800-899) meaning that we cannot tell exactly how much money was being spent on any one advert. Meanwhile, Google’s advertising archive contained errors that suggest it was not providing a complete overview of parties’ spend. Noting these shortcomings and recognising the imperfect nature of this data, we can nevertheless use this information to estimate campaign spend.

In reporting spend, we look at data from the Facebook and Google advertising archive. This was gathered as part of a wider project conducted at the University of Sheffield with the Department of Computer Science. Using the Application Programming Interface (API) provided by these companies, we analysed the adverts placed in the election period.

This analysis offers insight into what was spent. For example, looking at the amount spent by the national accounts of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties, we can see that while Facebook was used by all three national parties to a relatively equal extent, the Conservatives invested dramatically more in Google. The advertising archives suggest they spent £1,765,500, dwarfing the combined spend of £873,300 made by Labour and the Liberal Democrat accounts on this platform. Indeed, this data suggests that Labour spent just 36 percent of what the Conservatives did on Google, while the Liberal Democrats spent just 14 percent of their total. This mirrors reports that in the final days of the campaign the Conservatives were spending ‘fairly big money’ on a ‘YouTube homepage takeover’.

Figure 3: Total spend on Facebook and Google at 2019 general election by national Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat accounts as reported by advertising archives

However, this still only tells a part of the story. Focusing on Facebook, we see that adverts placed by the national party constituted only a fraction of the adverts placed by each political party. Indeed, within the Facebook ad archive, we found examples of adverts from candidates, local parties, regional parties, party groups and party leaders. So, if we focus on the headline figures, we do not get a full impression of the political campaign. If we include these other types of party campaigner, we see that Labour outspent the other parties, but that different groups in each party were responsible for different proportions of total spend.

Figure 4: 2019 general election party spend calculated for each type of party advertiser using data reported by advertising archives

Looking in more detail at spend is complicated as social media companies do not provide precise information about spending. This means that these results should be taken with a pinch of salt and should be seen to provide an approximation of spend, rather than a precise picture. This data nevertheless can be used to show the distribution of spending within different parties and offers interesting insights into how party organisation varies.

Looking at data from these transparency archives, we can therefore gain some insight into what campaigners were spending. Using the (admittedly limited) data available prior to the creation of these archives, the Electoral Commission reported that £3.16 million was spent on Facebook advertising by all UK parties at the 2017 general election, compared with just over £1 million on Google. While the advertising archives do not offer a completely reliable picture of what was spent (due to the way data is reported by Facebook), our analysis suggests that collectively political party spending on both platforms increased by over 50 percent, with around £6 million expended on Facebook and just under £3 million on Google. Before discussing the kinds of change that have been recommended to address these trends, it is important to consider what we still do not know about the money being spent on digital in election campaigns.

First, thinking about political advertising. The advertising archives offered by Facebook, Google and some other companies (such as Snapchat) provide some insight into what campaigns are doing online. However, these resources contain many flaws. The information provided is imprecise and difficult to analyse, with each company presenting different data in different ways – making it impossible to draw neat comparisons.

Moreover, not all digital providers offer this kind of insight, meaning there are other forums where digital advertising could be being run that we know nothing about. The lack of detail currently required on spending returns compounds this problem, as campaigners are under no obligation to specify where, precisely, money was spent. For example, spending on a YouTube advert could simply be recorded as ‘advertising’, meaning we cannot detect what was spent online or offline, or which digital platforms were used. These challenges (and others) mean that our picture of online political advertising is partial at best.

Second, looking beyond online advertising, it is also clear that money can be spent on other forms of digital campaigning activity. Campaigners can pay to boost posts on Facebook, they can launch influence campaigns and sponsor content – but these activities currently are not recorded in any archive. This means there is a raft of campaigning activity that is not transparent, making it difficult to determine if established regulatory principles are being violated.

What needs to change? Existing proposals

Recognising these limitations, we argue that it is currently exceedingly difficult (if not impossible) to uphold the above principles for regulation. This diagnosis is not new. A range of organisations have outlined proposals for reform. The Electoral Commission itself has been vocal in arguing for change and in 2018 issued a report that called for more transparency in digital campaigning. Regulators and campaigners also joined together to call for specific reforms in the Electoral Reform Society’s Reining in the Wild West report, and again in the report of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Electoral Campaigning Transparency’s 2019 inquiry.

Although different organisations have called for different types of change, there is broad consensus around the need for:

- Digital imprints that specify the name and address of who is promoting online campaign material and the name and address of any person on behalf of whom the material is being published (and who is not the promoter).

The government has recently launched a technical consultation to implement this idea, a development that should be welcomed. And yet, insights from the general election suggest that there are not only questions about who was spending money, but also about what was spent, where, and on what. Furthermore, there are questions about whether existing financial regulations are appropriate and sufficient, and whether further powers and resources are needed to regulate the online world. Indeed, reviewing a range of reports published in this area over recent years, we identify calls to:

- Require campaigners to provide the Electoral Commission with more detailed, meaningful and accessible invoices of what they have spent, and to subdivide spending returns to provide more precise information about online campaigning.

- Strengthen the powers of the Electoral Commission to obtain information outside of an investigation, to share information with other public agencies, to increase the maximum fine, to investigate and sanction candidates for breaking the rules.

- Implement shorter reporting deadlines so that financial information from campaigns on their donations and spending is available to voters and the Commission more quickly after a campaign, or indeed, in ‘real time’.

- Revise spending limits on party election and referendum spending to include campaign-related staff costs, and review spending and funding periods for referendums.

- Streamline national versus local spending limits with a per-seat cap on total spending and consider instituting per-annum spending limits.

- Regulate all donations by reducing permissibility check requirements from £500 to 1p for all non-cash donations, and £500 to £20 for cash donations.

- Amend the law so that all new parties and referendum campaigners with assets or liabilities over £500 have to submit a declaration of assets and liabilities upon registration with the Electoral Commission.

- Increase the length of the regulated period and define what constitutes political campaigning.

- Require platforms to maintain online advertising archives that contain the full range of political adverts (applying a common definition), and that provide consistent information about who funded an advert (as well as additional information – see the next section).

These recommendations reflect the currently fragmented and piecemeal nature of electoral finance law and have led to increasing calls for the government to:

- Rationalise electoral law under one consistent legislative framework.

Who was campaigning?

New groups and individuals

As evident in the discussion of money, existing regulation seeks to promote transparency and is designed to cast light on who is producing and funding campaign activity. As the Electoral Commission has argued, it is important that citizens ‘understand the origins of campaigning material’ and are ‘able to make a political choice with greater confidence’.

In recent years, however, developments in digital technology have made it more difficult to determine who is behind campaigns. By lowering costs, digital technology has made it easier for new groups and individuals to spread their ideas, and it is often not clear who these groups are or what their goal is. Created often just before an election, and quickly disappearing once the result is declared, these groups can provide little information about themselves. Indeed, if they spend below the threshold for registering with the Electoral Commission, they can get away with placing almost no identifying information in the public realm. This makes it hard to work out who is behind a political campaign and frustrates the ideal of transparency.

What are the rules?

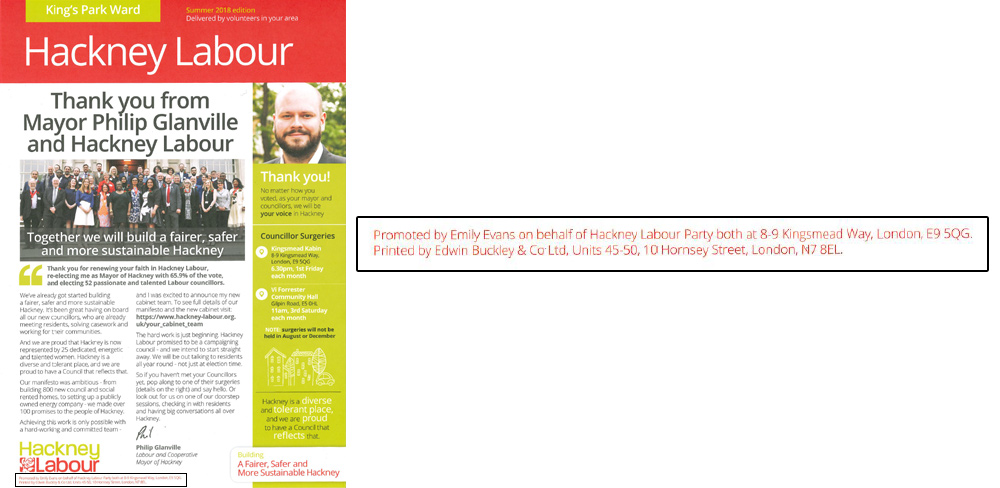

Historically, information about who is campaigning has been provided through a requirement for printed campaign material to contain what is known as an ‘imprint’ (specified in PPERA 2000). This is a declaration that appears on materials, such as leaflets, that must include:

- a) the name and address of the printer of the document;

- b) the name and address of the promoter of the material; and

- c) the name and address of any person on behalf of whom the material is being published (and who is not the promoter) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Example of a Labour leaflet containing an imprint

As the campaign environment has changed and gone online, this requirement has not been updated to apply to digital campaign material. This creates an inconsistency in electoral regulation (as only some campaign material contains an imprint) and is particularly problematic because in the digital realm it is easier for new (and unrecognisable) campaigners to get involved. Indeed, many digital campaigners are not large organisations with established reputations, but are small, short lived groups whose agenda and identity is hard for voters to pinpoint.

At present, the government is consulting on plans to implement a digital imprint. Although not yet finalised, it is proposing that the imprint contains the name and address of the promoter of the material; and the name and address of any person on behalf of whom the material is being published (and who is not the promoter). While this is a positive move, in the discussion below, we offer examples to show why this policy response is unlikely to be sufficient, and outline the proposals already made for further action to promote transparency around who is campaigning.

So, what do we know about campaigners active in the 2019 general election?

Available data about campaigners comes from the two sources discussed above – the Electoral Commission and company-provided transparency archives. From the same pre-poll donation data we can see the non-party campaigners that received donations over the £7,500 reporting threshold during the six weeks before election day. The ‘top five’ (i.e. those that garnered the most reported donations) were as follows:

- Best for Britain: £150,000

- HOPE Not Hate: £75,000

- More United: £49,000

- People’s Vote Media Hub: £40,000

- Real Change Lab: £40,000

The Electoral Commission also shows data on those non-party campaigns registered as spending over £20,000 in England or £10,000 in Wales in the year 2019. Sixty-four of these organisations registered in 2019 as a whole and 46 were registered after the election was (officially) confirmed on 29 October. Many of these were new organisations or bodies who had previously not been registered in election campaigns, suggesting an upsurge in campaigning activity from groups that voters may not be able to recognise. Moreover, registrations in 2019 showed a clear increase in this kind of activity from previous election years. 2017 saw the registration of 43 non-party campaigners, in 2015 there were 30, and in 2010 just 18 – showing that registered non-party campaigns have more than doubled since 2015.

The increase in non-party campaign groups can also be seen in information from advertising transparency sources. Looking at the data from the Facebook API, 88 organisations were coded as non-party campaign groups. These groups placed 13,197 adverts at a calculated cost of £2,711,452. Examples included ‘We Own It’ (registered on 20 November 2019), ‘Momentum’ (registered on 30 October 2019) and ‘Campaign Together’ (registered on 29 November 2019). In some instances, the amounts spent by these groups were sizable. For example, Best for Britain (registered on 28 April 2017), an organisation campaigning to ‘keep the UK open to EU membership’, spent £428,038 on Facebook adverts from October 9 2019 – largely around voter registration drives and tactical voting to prevent a Conservative majority / ‘Stop Boris’.

While campaign material from political parties and candidates is often easy to recognise, it can be difficult for voters to work out who is behind campaign material from a non-party actor. This makes it hard to know what agenda they are pushing and whether to trust the information they provide. The significance of this can clearly be seen in a number of examples from the general election.

Case Study 1: Fair Tax Campaign

The Fair Tax Campaign presents a useful example of a group with no clear history or longevity. On 13 October 2019, Facebook data records the group as being created, and on 14 November 2019, the group had its registration with the Electoral Commission approved. Looking at the advertising archive, it ran adverts from 1 November, and has not placed any ads, or had other activity on its Facebook page, since 12 December. During this period, the group had a reported spend of £63,105, and yet it is not clear who is behind this group. Facebook itself requires advertisers to provide their own form of ‘imprint’ specifying who paid for the advert. This information reveals that adverts were paid for by Alexander Karczewski Crowley and the Fair Tax Campaign – information that reveals little about the origins or intentions of this material.

Some clues are offered by the content of the adverts themselves, as the materials posted contained an anti-Labour message (see Figure 6). However, it is not clear whether this is being issued by an individual, by an unaffiliated campaign group, or by a group connected to a particular candidate or party.

Figure 6: An example of a Fair Tax Campaign advert

During the general election, journalists at the BBC undertook an investigation into this group after initial advertisements failed to display the disclaimer required by Facebook. This led to the discovery that the group was created by a former Downing Street aide who had worked with Boris Johnson. This information is likely to affect how these adverts are perceived, and yet it was not readily available to citizens on the advert itself.

Case Study 2: 3rd Party Ltd

A similar story emerged around the source and agenda behind a non-party campaign group called ‘3rd Party Ltd’. This group had its registration with the Electoral Commission approved on 13 November 2019, and created a Facebook group on 18th of the same month. It ran adverts from 21 November, with the last running on 13 December. In total this group spent £8,837 on Facebook adverts. As above, its agenda and affiliations were not immediately clear. Looking at the content of adverts, they initially offered a pro-Green Party message (Figure 7)

Figure 7: Initial adverts from 3rd Party Ltd

After a few weeks, however, the page started to place adverts in favour of Dominic Raab (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Later adverts from 3rd Party Ltd

An investigation by Wired found that the page was being run by an ex-Vote Leave staff member who had likely placed the Green adverts in an apparent attempt to split the Labour/Green vote. However, this information was not clear to advert viewers.

Similar examples can be found across the spectrum with groups such as ‘Make it Stop’ (registered on 21 November 2019) naming largely unknown individuals (in this case Justin Michael Elliot Smith) as the source of their campaign material (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Advert from Make it Stop

These examples suggest that a range of new organisations and groups are active in election campaigns. It also shows that it can be difficult to recognise these groups, or work out what their intentions are. This poses challenges, as some of these groups can be affiliated to parties, but not make those links overt. This makes it difficult for citizens, as the Electoral Commission suggests, to ‘understand the origins of campaigning material’ and ‘make a political choice with greater confidence’.

Proposals for change

Insights from the general election suggest that there is a case for further transparency around who is campaigning. Furthermore, there are also questions about accountability, as the short life span of many campaigning groups makes it unclear who should be held accountable if problematic practices are uncovered.

In response to these changes, a number of calls have been made for more information about the source of campaign material. As outlined above, the most common response has been to promote digital imprints. At the time of writing it is not yet clear how the government’s proposed model for imprints will help overcome cases where the source of a campaign appears to be designed to mislead an audience about who is responsible for a particular message.

Recognising this, it is important to note calls for action in other ways, including:

- Creating a publicly accessible, clear and consistent archive of paid-for political advertising. This archive should include details of each advert’s source (name and address), who sponsored (paid) for it, and (for some) the country of origin. There is some disagreement as to whether this archive should be independent, or whether consistent standards should be applied to existing advertising archives. However, there is widespread consensus that an archive should exist and that improvements are needed to current information disclosure.

- Defining what is meant by ‘political’ to establish clear remits for what should be included in a political advertising archive.

- New controls created by social media companies to check that people or organisations who want to pay to place political adverts about elections and referendums in the UK are actually based in the UK or registered to vote here.

- New legislation clarifying that campaigning by foreign organisations or individuals is not allowed, and that campaigners cannot accept money from companies that have not made enough money in the UK to fund the amount of their donation or loan.

- Requiring third-party organisations to complete an ‘exit’ audit after an election period.

- That the Electoral Commission should explore whether it would be feasible to create a secondary registration scheme for campaigners who would otherwise fall below current spending limits. These campaigners would only be required to register the identity of their trustees or legally responsible persons and the identity of their five largest funders. They would not be required to disclose spending. This information could then be used to improve the transparency of online imprints.

Who is seeing what?

Online targeting

An important principle often raised when it comes to elections is the idea that citizens should be able to access the same political information when exercising their political choice. As the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has outlined, it is essential that ‘political parties and campaigns operate from a level playing field when accessing the electorate, and that voters have access to the full spectrum of political messaging and information and understand who the authors of the messages are’.

This idea is important in the context of digital campaigning as technology makes it easier for campaigns to develop and communicate targeted messages to different groups online. This means that not all citizens will receive the same message, and it is also often impossible to see what information other people are being targeted with. This possibility is problematic as it could lead to different groups being promised different and potentially contradictory things, but it could also mean that certain groups of voters are ignored, while others (often in marginal constituencies) are bombarded with information.

In recent years, there have been calls for increased transparency about online targeting. The Electoral Commission has suggested that a primary issue is ‘[o]nly the voter, the campaigner and the platform know who has been targeted with which messages. Only the company and campaigner know why a voter was targeted and how much was spent on a particular campaign’. This indicates there is a case for rethinking current requirements in the online and offline world around targeted messaging.

What are the rules?

Although there have been widespread concerns voiced about targeted messaging online, the practice is not new and has not historically been seen as inherently controversial. Indeed, it has long been common practice for campaigners to direct different messages to different groups. This has meant that canvassers may only knock on some doors, or that different pieces of direct mail are sent to different groups of voters. The practice of targeting and information disclosure around targeting are not, therefore, currently part of electoral regulation.

So, what do we know about targeting in the 2019 general election?

t present, no regulatory body collects data on targeting, although the Electoral Commission has asked for the power to require targeting information on invoices (see below). Some limited information is, however, provided by company transparency archives.

Looking at the Facebook advert archive, the information provided about targeting is sparse. We can only see information on the number of advert impressions, the gender and age breakdown of viewers, and the region in which the advert was viewed (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Targeting information on Facebook’s advertising archive

As with information about spending, targeting insights are given in broad brackets (e.g. between 2k-3k impressions) or as percentages, making it impossible to determine exactly how many people (of different ages and genders) saw the advert.

It is also clear that this is only part of the picture. When looking at the categories Facebook provides for targeting, a whole range of different options are presented. These include more fine-grained options for location (such as cities or local communities), demographics (such as education and job title), interests (such as hobbies or personal preferences), behaviour (such as prior purchase information) or connections (i.e. who people are connected to on Facebook). No information is, however, provided by the Facebook advertising archive about these targeting criteria, making its mechanics unclear.

Other platforms, such as Snapchat, provide considerably more detailed information with regards to how adverts are targeted, inclusive of regions, electoral district (constituency), and radius targeted. However, while Snapchat presents an example of better practice, it remains a relative minnow in terms of overall spend at elections.

Some attempts have been made by journalists and civic campaign groups to provide more insight into the targeting criteria used by campaigns. The BBC, for example, created a crowd-sourcing project that asked voters to send in screenshots of the ‘Why Am I Seeing this Ad’ information that Facebook provides to users. This provided additional information and often showed that advert recipients were seeing material because an advertiser had uploaded a list of recipients that they wanted to reach. It also showed a tendency for adverts to be targeted at marginal constituencies and certain demographic groups. For example, early in the election campaign, the Conservatives pitched adverts about social services to women, while men received a ‘Get Brexit Done’ message.

Similar insights were also provided by Who Targets Me, a campaign that used a Google Chrome extension to gather data about the attributes of individuals receiving adverts. The resulting analysis was able to show a significant focus on certain constituencies, attempts by different parties to reach out to different groups of voters across the campaign, and the use of different messages to different voters. For example, they showed that the Conservatives had three specific types of advert, an ad that featured Boris Johnson and the opposition, an ad that featured Boris Johnson alone, and an ad that featured just the opposition. Who Targets Me found that in Remain-leaning seats, adverts solely featuring the opposition were favoured, whereas those in Leave-voting seats tended to solely feature Johnson.

These data sources provide some detail on the kind of differences that were apparent in targeting, but there is much that it is not possible to know. While initiatives such as crowd-sourcing and Who Targets Me can provide a window into campaigners’ strategies, they do not capture activity across the whole of the country – only picking up the trends observed by those who choose to email in targeting details or install the Who Targets Me extension (people who tend to be educated to a higher level, affluent and often left-leaning).

There is a lack of information that is equally evident offline and online. Campaigners do not, for example, have to say where and how leaflets or other forms of non-digital campaign material were targeted. While this could be seen as a reason not to require action, the rise of technology has made new forms of data available and has changed the dynamics of campaigning. These changes make it important to revisit established principles to determine if and how electoral law needs to continue to evolve.

Proposals for change

The general election has shown that we know very little about digital targeting activity across the country as a whole. It remains unclear whether only some voters are being contacted by campaigns, whether people are being presented with different (and potentially contradictory) messages and whether campaigners are using personal information that we are comfortable with. This absence of information matters, because the Electoral Commission has found through public opinion research that people are worried about targeted messages, but it is not clear whether they are right to be concerned.

In response to these changes, a number of calls have been made for more information about targeting. These include:

- To require campaigners to provide the Electoral Commission with more detailed, meaningful and accessible invoices of what they have spent.

- There should be full disclosure of the targeting used as part of advertising transparency. The government should explore ways of regulating the use of external targeting on social media platforms, such as Facebook’s Custom Audiences.

- The creation of an ‘online harms regulator’ which has formal coordination mechanisms with the ICO and the Competition and Markets Authority.

- Researchers should be provided with secure access to data, where this research is of significant (potential) importance.

- The creation of a ‘code of practice’ which sets appropriate standards with regards to targeting and will require online platforms to both assess and explain the impact of targeting.

Political parties (and non-party campaigns) should work to the same rules as it relates to data protection and marketing laws (as set out by the ICO draft code of practice).

How is data used by campaigns?

The regulation of data

Tied closely to debates around targeting, there is also concern about the way that campaigners are using data. Historically, it has been accepted that it is democratically beneficial for campaigners to contact voters and acceptable to gather and use data to shape those interactions. To facilitate this process, political parties have been provided with access to the electoral roll, providing them with data on the electorate. Building on this resource, parties and other campaign groups have collected further data to build up a picture of people’s voting preference, interests and needs, and to tailor their campaigning activity. Such actions are a valuable part of election campaigns, they stimulate democratic engagement and participation.

With the rise of digital technology, however, the issue of data use by campaigns has become more controversial as digital technology has made it possible to gather and/or buy more detailed information about citizens. This information can often be gathered without an individual’s knowledge and consent, and can be used to target people with different information. This has raised questions about the regulation of data and what acceptable practice looks like. The ICO in particular has raised concerns about this kind of ‘data-driven campaigning’, arguing that:

‘unlike more traditional forms of campaigning, these techniques are – by their nature – more opaque. Messages are often received in an ‘echo chamber’ online, where voters may not hear the other side of the argument. Voters may not understand why they are receiving particular messages, or the provenance of the messages’.

Given the importance of transparency, this has led to calls for reform, but there has also been attention directed to the need to think about what kind of data it is acceptable to use in campaigns and whether it is okay for campaigners to use data without an individual’s consent.

What are the rules?

When it comes to data use by campaigners, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) specify principles for the responsible use of data. The DPA 2018 legislates that political opinions should be protected, that consent is essential for the storage and use of data, and that information should be kept accurate and up to date. As outlined in Ravi Naik’s detailed report on data protection law, these principles create specific expectations around the use of data.

When it comes to political campaigners use of data, an exception to the DPA has allowed these restrictions to be circumvented. Specifically, an exemption allows for the use of most data (excluding special category data) when that use is in the public interest. This is specified to include ‘an activity that supports or promotes democratic engagement’. Under these circumstances, campaigners can use data to communicate with electors, campaign, gather opinion and attempt to boost turnout, without needing to gain explicit consent from the subject. Although ‘special category data’ is subject to further protection, it is also possible for parties to process this information when it ‘is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest’.

Existing data protection law therefore facilitates the collection and processing of data by parties and campaigners.

So, what do we know about data use at the 2019 general election?

At present our insights into data use at the election are extremely limited. In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, parties and campaigners have become even more cautious about disclosing information about their campaigning strategy and approach. This means that there are few insider accounts from those responsible for using data to construct a campaign strategy, and little insight into how data is collected (online and offline) and analysed.

Recent investigative work by the Open Rights Group has allowed for some understanding of the kind of data that parties are collecting. It showed that parties stored information that estimated whether a person had children or not, how much money an individual makes, how strongly they supported the party in question, how old they were, and whether their mother tongue was English (amongst others). This shows that parties gather and store a range of information about voters, but it is not clear how or whether this is used to target campaigning activity.

There are some indications of how parties and other campaigners could be making use of these insights. Platforms such as Facebook, for example, allow parties to upload lists of email addresses to their system so that voters can be ‘matched’ to social media profiles. These matched contacts can then be reached directly using Facebook advertising, or they can be used to identify ‘lookalike’ audiences: groups of voters who possess the same kinds of characteristics as those on the uploaded list. Social media companies can therefore provide a powerful tool for using existing data or gathering new insights on voters.

Proposals for change

The general election has further confirmed that we know very little about current practices. While this kind of data use can be justified in line with the exemptions outlined above (a defence used by parties to explain their data use), there is evidence that some of the activities being undertaken are raising public concerns. In particular, the Open Rights Group has called for more detailed reflection on what activities are and are not permissible under the ‘democratic engagement’ provision.

The issue of data use in elections is gaining growing attention and calls have already been made to:

- Increase collaboration between parties, the ICO, Cabinet Office and Electoral Commission to implement a cross-party solution to improve transparency around the use of commonly held voter data.

- Hold public information campaigns around citizens’ data rights designed to increase transparency and build public trust.

- Legislate for a statutory code of practice for the use of personal information in campaigns.

- Ensure third party audits are carried out after referendum campaigns are concluded to ensure personal data held by the campaign is deleted, or if it has been shared, the appropriate consent has been obtained.

- Ensure platform compliance with GDPR so that users understand how personal information is processed and that effective controls are available.

- Review the scope of the ‘democratic engagement’ provision in the DPA 2018 and more clearly specify what constitutes acceptable practice with regards to parties’ use of personal data.

- Encourage political parties to move to a consent based opt-in model of political profiling.

What is being said?

Claims of mis- and disinformation

Finally, an important issue to emerge in the 2019 general election was the veracity of claims being made by campaigners. Claims of mis- and disinformation have not historically been at the centre of electoral regulation, but are becoming increasingly prominent in debates around digital campaigning. The rise of online campaigning and the proliferation of new voices can make it hard to know who to trust and what information is correct. This trend is problematic because ensuring that voters have good information to make an informed choice about how to vote is an important democratic principle.

The content of online campaign material, unlike broadcast material, is currently not subject to regulation. This means that both organic content and political advertising does not need to adhere to any standards of accuracy. So, while non-political advertising is required to be ‘legal, decent, honest and truthful’, political advertising is not held to the same standard.

During the 2019 general election, the Coalition for the Reform of Political Advertising reported polling that found that 87 percent of voters believe ‘it should be a legal requirement that factual claims in political adverts must be accurate.’

What are the rules?

There are rules surrounding misinformation in commercial advertising, which are regulated by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). The basic principle underpinning the ASA’s work is that adverts must be ‘legal, decent, honest and truthful’. The Committee of Advertising Practices (CAP) writes codes to which advertisers are expected to adhere. While the ASA can refer offenders to trading standards and have legal powers for enforcement, this does not translate to the world of political advertising. Up until 1999, non-broadcast political advertising was subject to the same rules, but following the 1997 general election, the decision was made to exclude political advertising from the ASA’s remit.

Another relevant regulation can be found in Section 106 of the Representation of the Peoples Act 1983. This makes it a crime to publish any false statement of fact in relation to a candidate’s personal character or conduct, unless the person in question can show that they had ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing the statement to be true. Section 106 is rarely used. One of the few examples that can be found concerns Labour Councillor Miranda Grell, who was the first person convicted under this rule in 2007 after she accused her Liberal Democrat opponent of paedophilia. During the 2019 general election, Section 106 was used to prevent the Royal Mail from distributing SNP literature which made false claims about Liberal Democrat Leader Jo Swinson.

Therefore, while there is some existing regulation around false claims in elections with regards to candidates, its scope is relatively narrow.

So, what do we know about misinformation in the 2019 general election?

Throughout the general election campaign there were several high profile examples of dishonest or misleading claims by parties (across the political spectrum), and non-party campaigns that fall outside of the scope of current regulation.

Video Doctoring

On 5 November, the Conservative Party shared a tweet (Figure 11) that claimed to show (then) shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer struggling to answer a question about Labour’s Brexit policy. This video was widely shared online, receiving over one million views, but it quickly emerged that the video had been doctored. As a review by the fact checking organisation Full Fact concluded, the video was ‘untrue. In the original video, Mr Starmer answers promptly. His reaction in this video has been edited’.

Figure 11: Screenshot of Conservative Party tweet

Fake websites

The election also saw examples of campaigns creating ‘fake’ websites that sought to misrepresent the positions of opposing political parties. Examples included pages appearing to represent the Conservative Party such as www.thetorymanifesto.com (Figure 12) that contained a range of expletive laden ‘policy pledges’. A similar page www.labourmanifesto.co.uk made clear it was made by the Conservative Party.

Figure 12: Screenshot of The Tory Manifesto website

These websites were created cheaply, contained only limited content and, in the case of www.labourmanifesto.co.uk, was even promoted through Google advertising. A similar example came in the form of the Conservative Party’s renaming of its Twitter handle from ‘CCHQPress’ to ‘FactCheckUK’, in an attempt to ape genuine (independent) fact checking services, during the ITV leadership debate.

These examples have fuelled calls for regulation of misleading content, with observers arguing that these practices have the potential to mislead voters and to undermine trust in politics. However, any reforms must be undertaken with care. There (rightly) remains much concern about the effect that any centralised control might have on fundamental principles that underpin any democratic society, such as freedom of the press, and freedom of speech.

Proposals for change

- In response to these developments, a number of calls have been made for changes to bring about more truthful election campaigns. These include:

- Political parties should work with regulators and the advertising industry to develop a code of practice for political advertising – along with appropriate sanctions – that restricts fundamentally inaccurate advertising during a parliamentary or mayoral election, or referendum.

- Ofcom should produce a code of practice on misinformation. This code should include a requirement that, if a piece or pattern of content is identified as misinformation by an accredited fact checker, then it should be flagged as misinformation on all platforms. The content should then no longer be recommended to new audiences. Ofcom should work with platforms to experiment and determine how this should be presented to users and whether audiences that had previously engaged with the content should be shown the fact check.

- Ofcom should work with online platforms to agree a common means of accreditation (initially based on the International Fact Checking Network), a system of funding that keeps fact checkers independent both from government and from platforms, and the development of an open database of what content has been fact checked across platforms and providers.

- Parliament should establish formal partnerships with broadcasters during election periods to make optimal use of its research expertise to help better inform election coverage.

- Social media companies should commit to publishing any instances of disinformation. The government needs to ensure that social media companies share information they have about foreign interference on their sites— including who has paid for political adverts, who has seen the adverts, and who has clicked on the adverts—with the threat of financial liability if such information is not forthcoming.

- The government should establish an independent ombudsman for social media content moderation to whom the public can appeal, should they feel they have been let down by a platform’s decisions. The ombudsman’s decisions should be binding on the platform, transparently published and in turn create clear standards to be expected in future.

- A public awareness and digital literacy campaign should be implemented which will better allow citizens to identify misinformation.

Conclusion

Digital elections

The 2019 general election was heralded by many as the ‘digital election’. While the result showed that many historic truths with regards to electoral politics remain, we are facing a rapidly changing, ‘Wild West’ in campaigning. Despite the rise of challenger parties, First Past the Post ensured that politics, in England at least, (largely) remains a two-player game. All the while politics was increasingly conducted online, such that our electoral systems have become stretched to breaking point.

In a previous ERS report, it was argued that there had been a ‘fundamental shift in the ways in which political campaigns are conducted’. We agree. In this report we have outlined five areas in which electoral law in the UK is not fit for purpose:

- Money

- Non-party campaigns

- Targeting

- Data

- Misinformation

By posing questions that relate to each topic, we have highlighted the many areas where recommendations have already been made, not just by campaign organisations but by parliamentary select committees and regulators themselves. The government has so far taken little action to progress these ideas. Instead, we have seen threats issued about the future of the Electoral Commission and limited commitments to further change. The evidence in this report makes clear, however, that there is an urgent need for expansive change – not least given the major round of elections coming up in May 2021, alongside growing fears around foreign interference.

The new Wild West of political campaigning need not merely present a challenge. The changing political landscape creates exciting opportunities for different ways of doing politics and enhanced avenues for citizen engagement. Initial reforms, however, need to consider the many ways in which this world remains shrouded in secrecy. We must build a framework for online campaigning which brings out the best in us, and which engenders public confidence. But to make the most of these opportunities and meet these challenges we urgently need reform.

Further Reading

- APPG on Electoral Campaigning Transparency (2020). Defending our Democracy in the Digital Age: Reforming Rules, Strengthening Institutions, Restoring Trust. Available at: https://fairvote.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Defending-our-Democracy-in-the-Digital-Age-APPG-ECT-Report-Jan-2020.pdf

- Coalition for the Reform of Political Advertising (2019). Illegal, Indecent, Dishonest & Untruthful: How Political Advertising in the 2019 General Election Let Us Down. Available at: https://reformpoliticaladvertising.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Illegal-Indecent-Dishonest-and-Untruthful-The-Coalition-for-Reform-in-Political-Advertising.pdf

- Dommett, K. (2020). Introduction: Regulation and Oversight of Digital Campaigning – Problems and Solutions. The Political Quarterly, online first. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-923X.12888?af=R

- Dommett, K. and Bakir, M.E. (2020). A Transparent Digital Campaign: The Insights and Significance of Political Advertising Archives for Debates on Electoral Regulation. In: Tonge, J., Wilks-Hegg, S. and Thompson, L. (eds.) (2020). Britain Votes: The 2019 General Election. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dommett, K. and Power, S. (2019). The Political Economy of Facebook Advertising: Election Spending, Regulation and Targeting Online. The Political Quarterly, 90(2), pp. 257–65.

- Electoral Commission (2018). Digital Campaigning: Increasing Transparency for Voters, London: Electoral Commission. Available at: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/changing-electoral-law/transparent-digital-campaigning/report-digital-campaigning-increasing-transparency-voters

- Electoral Commission (2020). 2019 UK Parliamentary general election. London: Electoral Commission. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/elections-and-referendums/past-elections-and-referendums/uk-general-elections/report-overview-2019-uk-parliamentary-general-election

- House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee (2019). Disinformation and ‘Fake News’: Final Report (Fifth Report of Session 2017–19). London: HMSO. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf

- House of Lords Select Committee on Democracy and Digital Technologies (2020). Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust (Report of Session 2019-2021). Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5801/ldselect/lddemdigi/77/77.pdf

- Information Commissioner’s Office (2018). Democracy Disrupted? Personal Information and Political Influence, London: HMSO. Available at: https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/2259369/democracy-disrupted-110718.pdf

- Information Commissioner’s Office (2019). Guidance on Political Campaigning: Draft Framework Code for Consultation. Available at: https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/consultations/2615563/guidance-on-political-campaigning-draft-framework-code-for-consultation.pdf

- Naik, R. (2019). Political Campaigning: The Law, the Gaps and the Way Forward. Available at: https://oxtec.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/115/2019/10/OxTEC-The-Law-The-Gaps-and-The-Way-Forward.pdf

- Palese, M. and Mortimer, J. (eds.) (2019). Reining in the Political ‘Wild West’ Campaign Rules for the 21st Century. London: Electoral Reform Society. Available at: https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/latest-news-and-research/publications/reining-in-the-political-wild-west-campaign-rules-for-the-21st-century/

- Who Targets Me (2020). Ten Simple Ideas to Regulate Online Political Advertising in the UK. Medium, 4 June. Available at: https://medium.com/@WhoTargetsMe/ten-simple-ideas-to-regulate-online-political-advertising-in-the-uk-52764b2df168

About the authors

Dr Katharine Dommett is Senior Lecturer in the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield. Her research focuses on digital campaigning and the role of technology in democracies. She recently served as Special Advisor to the House of Lords Select Committee on Democracy and Digital Technologies and was awarded the Political Studies Association’s Richard Rose Prize for an early-career scholar who has made a distinctive contribution to British politics. In 2020 she published her book, The Reimagined Party, and is the author of over 30 academic journal articles.

Dr Sam Power is Lecturer in Corruption Analysis at the University of Sussex. His research focuses on political financing, online campaigns and corruption. He has published widely on these themes in both academic and non-academic publications. His book, Party Funding and Corruption, was published in 2020 through Palgrave.

This report is based on research conducted with support from the British Academy, grant number EN\170107. It also draws on the findings of a collaborative research project between the Department of Computer Science and Department of Politics at the University of Sheffield. We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Mehmet Bakir, Kalina Bontcheva and Muneerah Patel to this work. The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of Benjamin Mason who provided additional research support on receipt of a Junior Research Associate Scholarship from the University of Sussex.